The Director's Corner

April 8, 2025

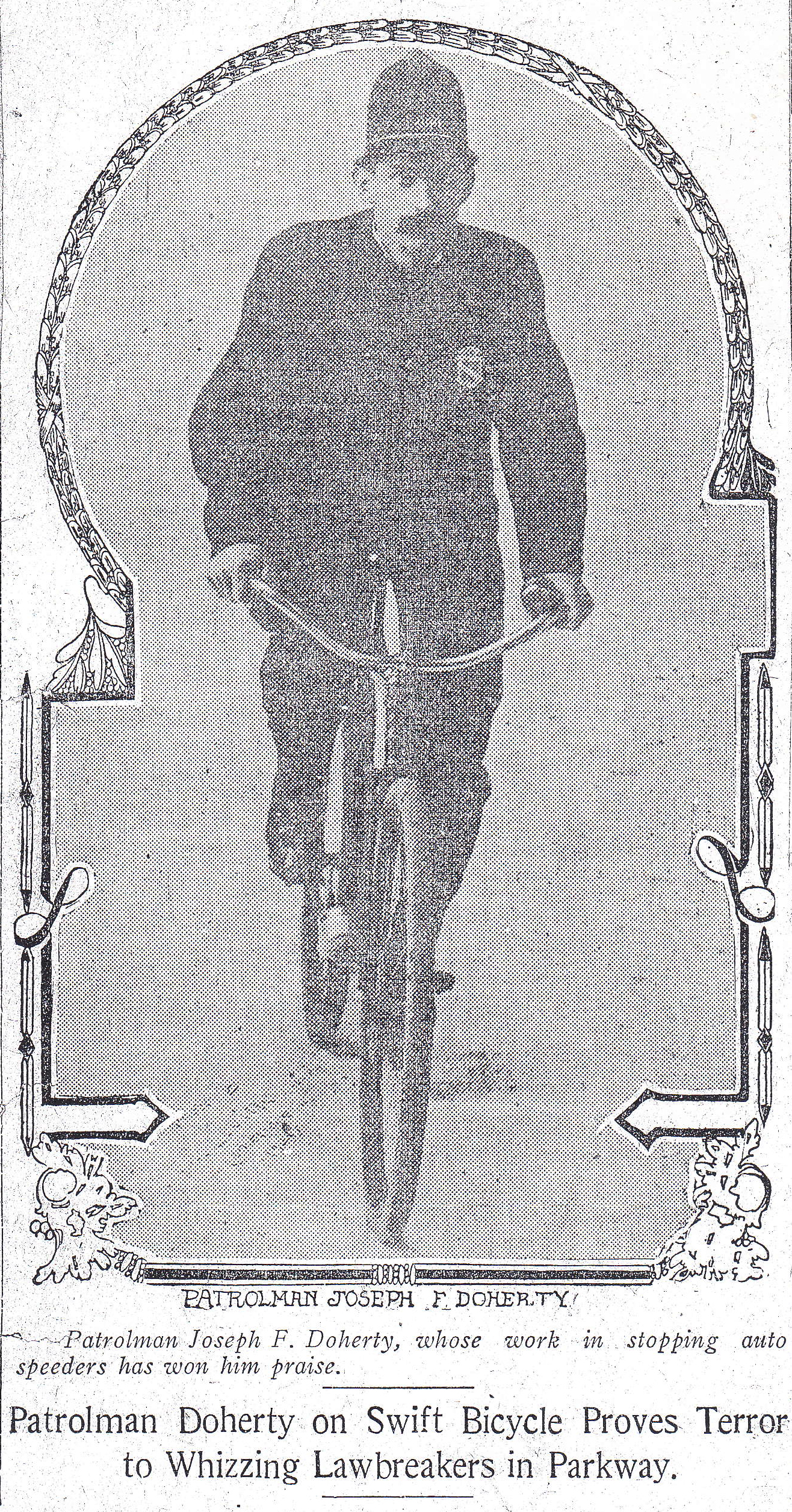

On my desk, next to my computer, I keep an old black-and-white photograph of a uniformed policeman on a bicycle. The man in the photo, Joseph F. Doherty, who went by “Joe,” was one of my great-grandfathers on my mother’s side. I keep the photograph there because it helps me feel connected to my family, but also because it reminds me of what I care about the most as a scholar, educator, and director of Auburn’s Honors College.

I tend to think of police officers being assigned to bicycles for areas where patrol cars cannot easily travel, such as parks and college campuses. The story behind my great-grandfather’s photograph, however, is quite different. It comes from a newspaper article of 1907 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Joe very recently had been made a regular patrolman. The article described his assignment as the first bicycle patrolman in the city, which the chief of police had ordered in response to a citizen petition about the dangers that the growing number of reckless motorists were posing to pedestrians. Joe was well known for his athleticism, having won trophies as a runner and bicycle racer, and the article noted that his “swift Bicycle” had become a “Terror to Whizzing Lawbreakers” on the Charles River Parkway. The article announced that he already had chased down more than 20 motorists and given them court summons, which had resulted in stiff fines and much safer roadways.

Many of us think of ourselves today as living in an era of unprecedented and rapid change. Rapid, yes, but unprecedented, no. Daunting as it is to forecast what our world will look like in a decade, let alone how best to prepare young minds to flourish in it, I don’t think our world is in less dramatic upheaval than was the world into which my great-grandfather was born in 1881. The son of a man who, at the age of nine, became one of two million people fleeing Ireland for the United States during the potato famine, he was part of a dramatic time of change in Boston and Cambridge, and indeed in the world at large. Even as Boston and Cambridge absorbed a massive influx of immigrants who altered the ethnic and religious composition of that region, humanity in general was in an unprecedented phase of adjustment to new technologies from the industrial revolution, including combustion engines and automobiles.

AI is here, geopolitical and economic alignments are in flux, expectations of education are changing, and so too are attitudes to universities. These things are new, but the fact of newness is quite old. The ancient philosopher Heraclitus famously is reputed to have said, “πάντα ῥεῖ,” often translated as, “the only constant is change.” How true.

I am here in this job because I believe in the power of education to prepare humans to flourish in their futures and to improve the world into which we send them as new graduates. What exactly educators are preparing our students for is unknown. That is entirely the point. We are not just training them for specific tasks and jobs; we are preparing them to adapt to the things we can’t yet see coming. Sometimes that adaptation entails embracing new technologies, new languages and texts, new cultures and ways of working. Sometimes it entails using older ones, as when my great-grandfather chased down new automobiles with a bicycle. Honors education, I believe passionately, can give students those extra layers and components of learning. In the Honors College we call our students to respond more actively to what they are being taught. We instill a deep awareness of what it means to inhabit one discipline and collaborate effectively with those inhabiting other ones. We also teach our students to remember what is old, especially what is tried and tested, even as they prepare to address what will be new. I imagine all our Honors students, in one way or another, going into the world as my great grandfather did, chasing down the hazards and challenges of the future in whatever way they find works best -- sometimes with new methods, but also with older ones, racing swift bicycles against automobiles, for the good of their communities.

Dr. Laura Stevens

Director, Honors College

Professor of English